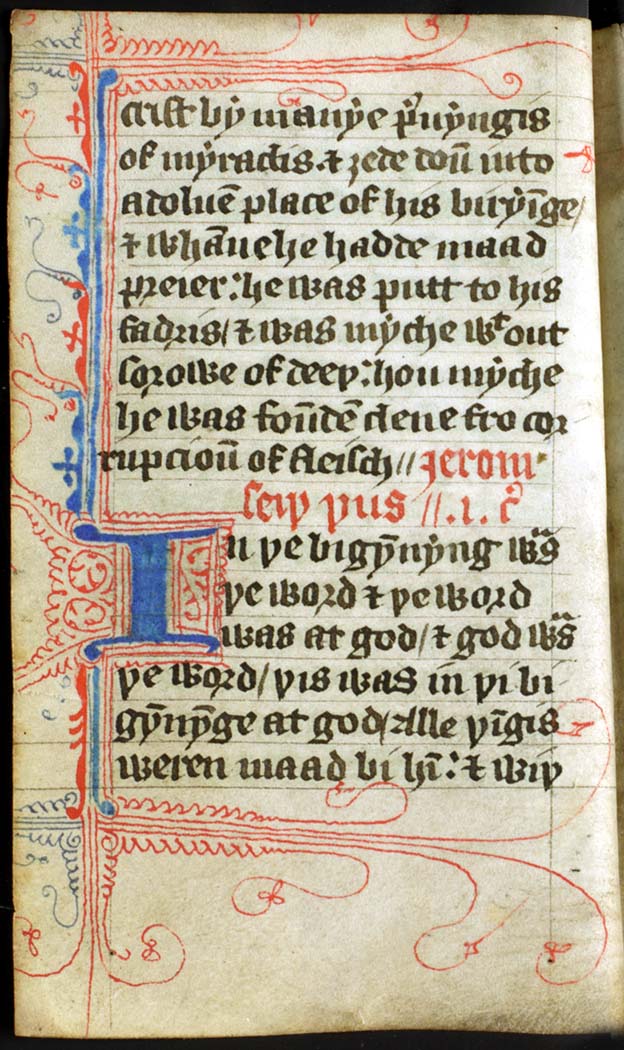

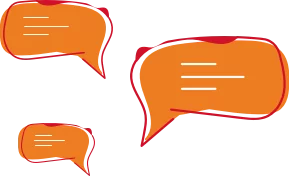

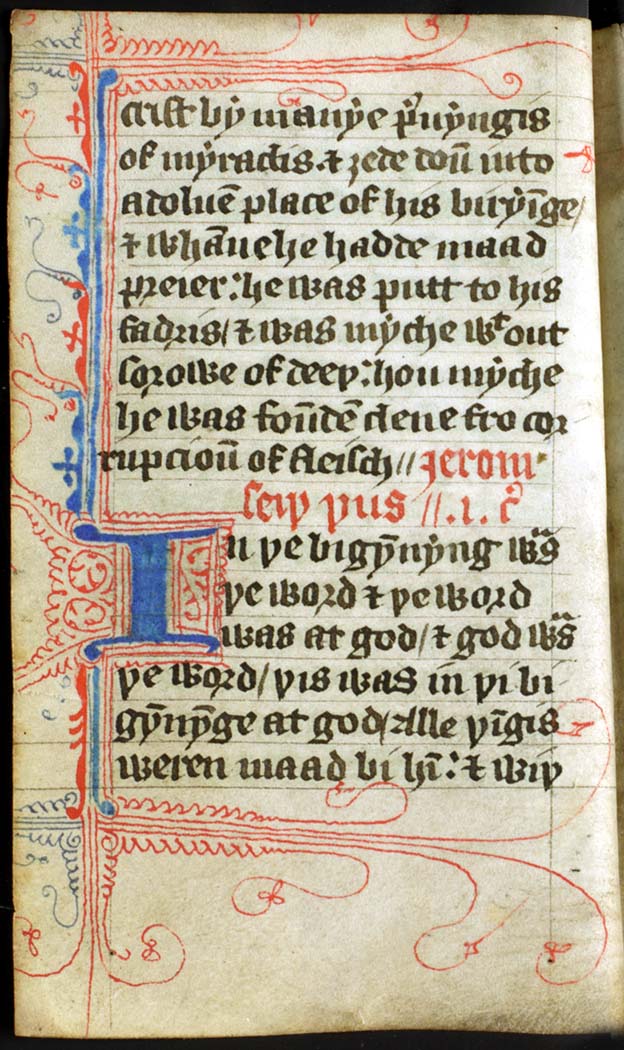

John’s Gospel in a Wycliffe Bible

John’s Gospel in a Wycliffe Bible

Do you know what these words mean? Most people living in England in the 1330s didn’t. They understood English, not Latin – and it is largely thanks to John Wycliffe that we can understand them in English today.

Accused of heresy

The verse is John 14:6, which says: ‘Jesus answered, “I am the way and the truth and the life. No-one comes to the Father except through me.”’

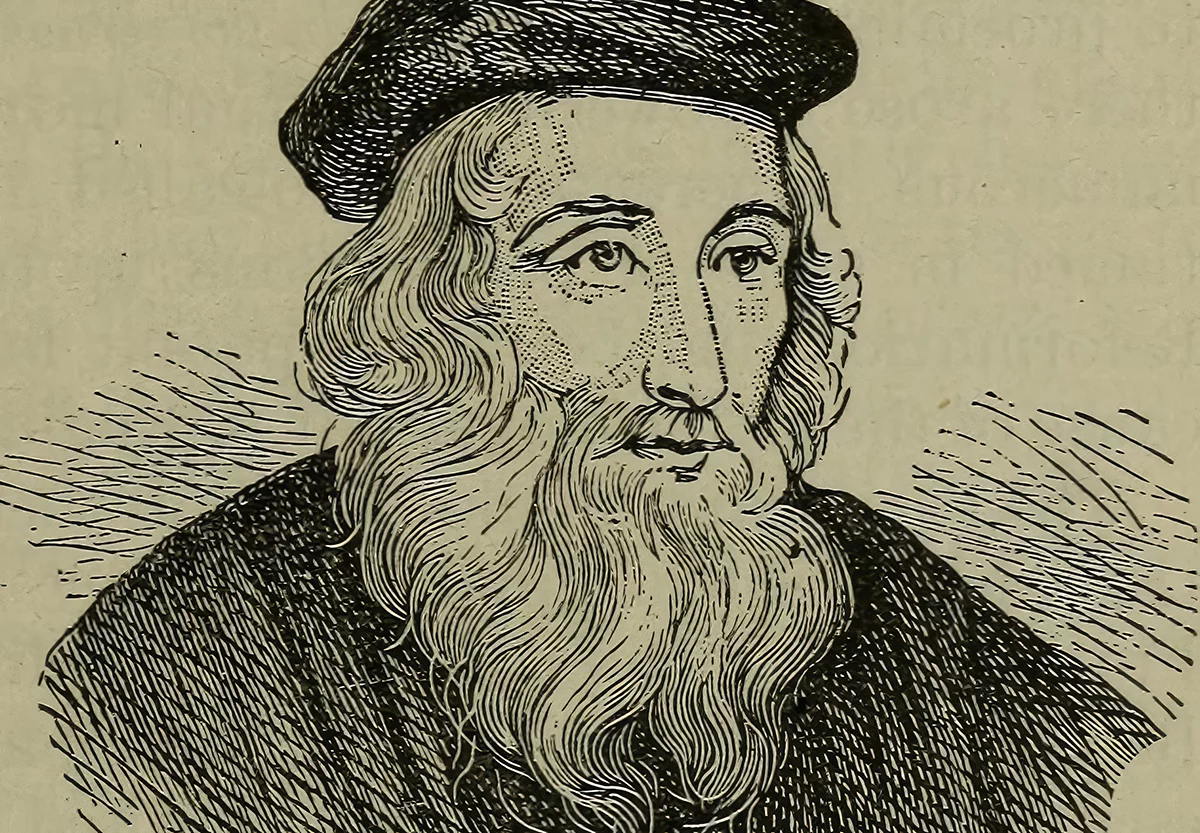

John Wycliffe was the first translator of the English Bible. Throughout his life he became convinced of the need to translate the Bible into English. This conviction had deepened through his years of devotion to following Jesus – his years of studying the truths of the Bible. His years as one of the leading theologians in one of the leading universities in the world. Those years when he challenged where the teaching of the Church had departed from the teaching of the Bible. The years he was accused of heresy. The years he was put on trial – years when he was rejected and banished from his beloved Oxford. And the years when it looked like he had failed to bring about the change he knew the Church needed.