It really does seem that Bible translation has always been integral to God’s mission. Nowhere is this more striking than in the early Syrian Church. Amazingly, the Church that Saul intended to persecute in Acts 9 became a centre for mission. The first translation of the Scriptures in the Christian era was into Syriac around 170 AD, as spoken in Damascus!

Bible translation activity then spread out from Syria over the following centuries into Armenia, Georgia, Samarkand and beyond. The Septuagint was almost always the source text for the Old Testament at this stage. This was a translation from Hebrew into Greek, completed around 130 BC, for Greek-speaking Jews. It was what Paul used when quoting the Old Testament. You know what they say: ‘If it was good enough for Paul, it’s good enough for…’

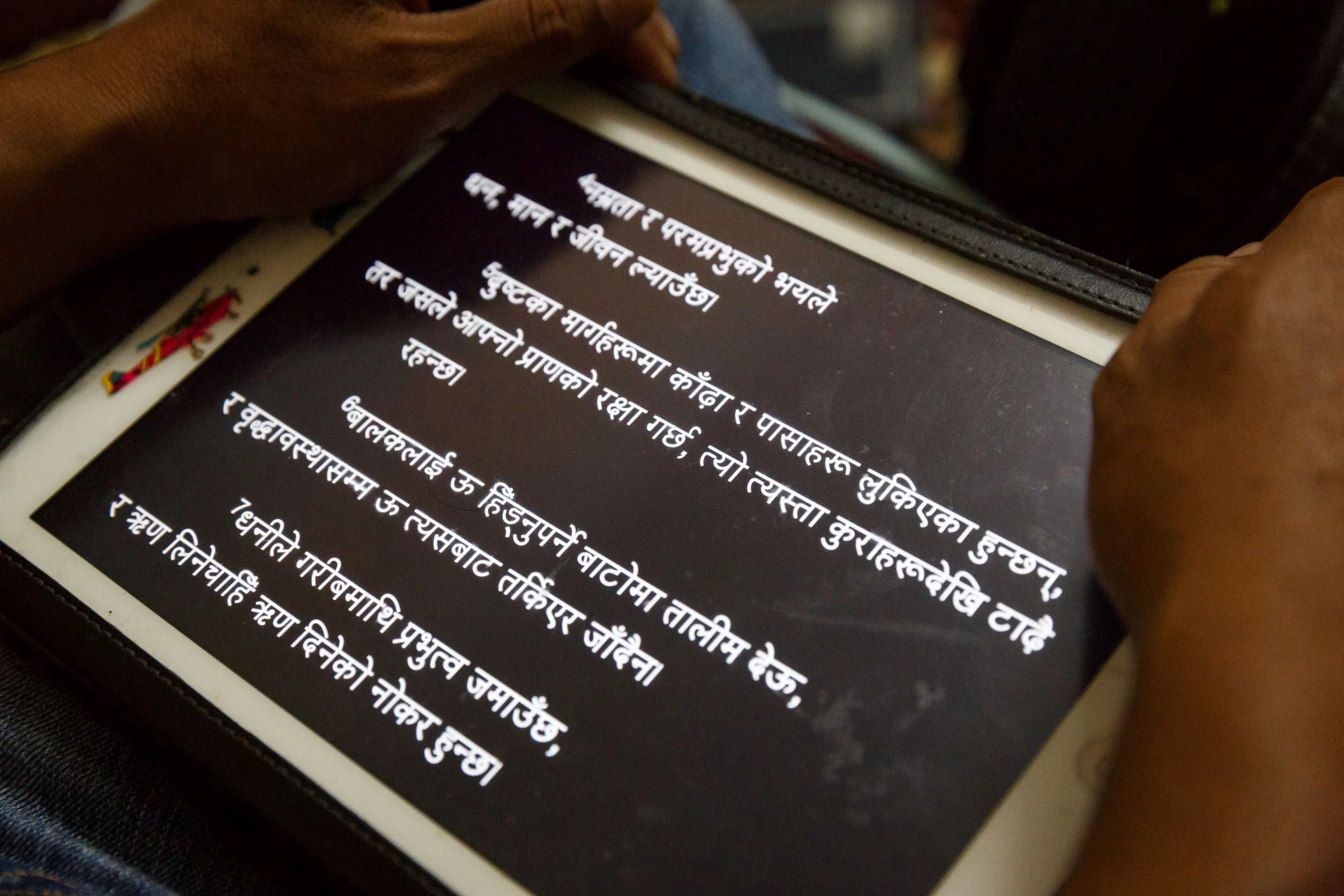

Making the Scriptures available to ordinary people

One man not convinced by this argument was Jerome. Around 382 AD the Pope commissioned his secretary, Jerome, to produce a new translation in Latin, as the Septuagint-based versions were, shall we say, rather messy. Jerome set about the task with reported trepidation, but also with great seriousness. He learnt Hebrew and, thanks to the work of Origen, was able to access Scripture texts in both Hebrew and Greek. The remark, attributed to him, that ‘ignorance of Scripture is ignorance of Christ’ reveals something of his passion.

The resulting translation, produced in the Latin of the people, is known to us as the Vulgate. We scarcely realise how many of Jerome’s key terms we have adopted into English. Words like Scripture, salvation, justification and regeneration made their way into English via their Latin form in the Vulgate.