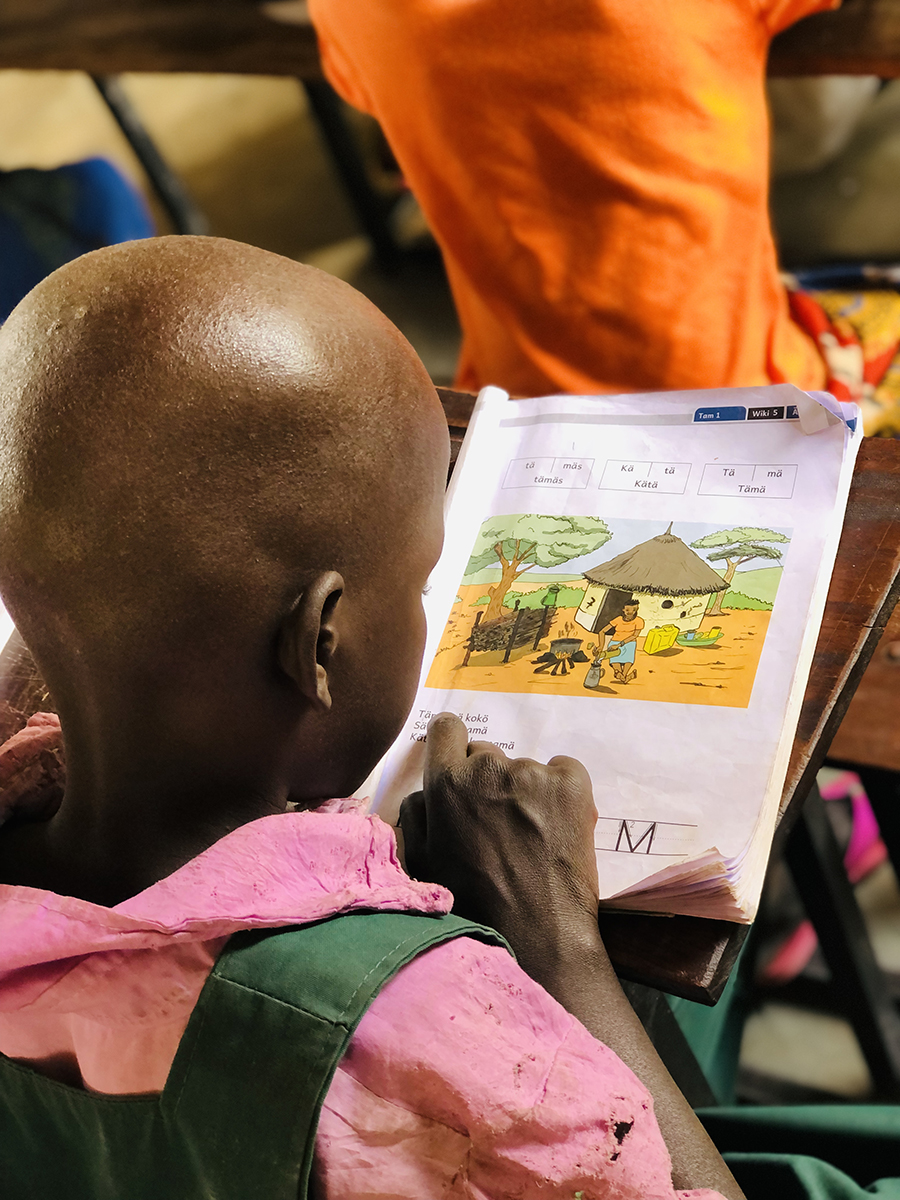

Kipkemboi* loves learning and is looking forward to going to school. All his friends are going and it will be lots of fun.

He arrives on his first day of primary school and is excited to see his friends. They, too, are excited.

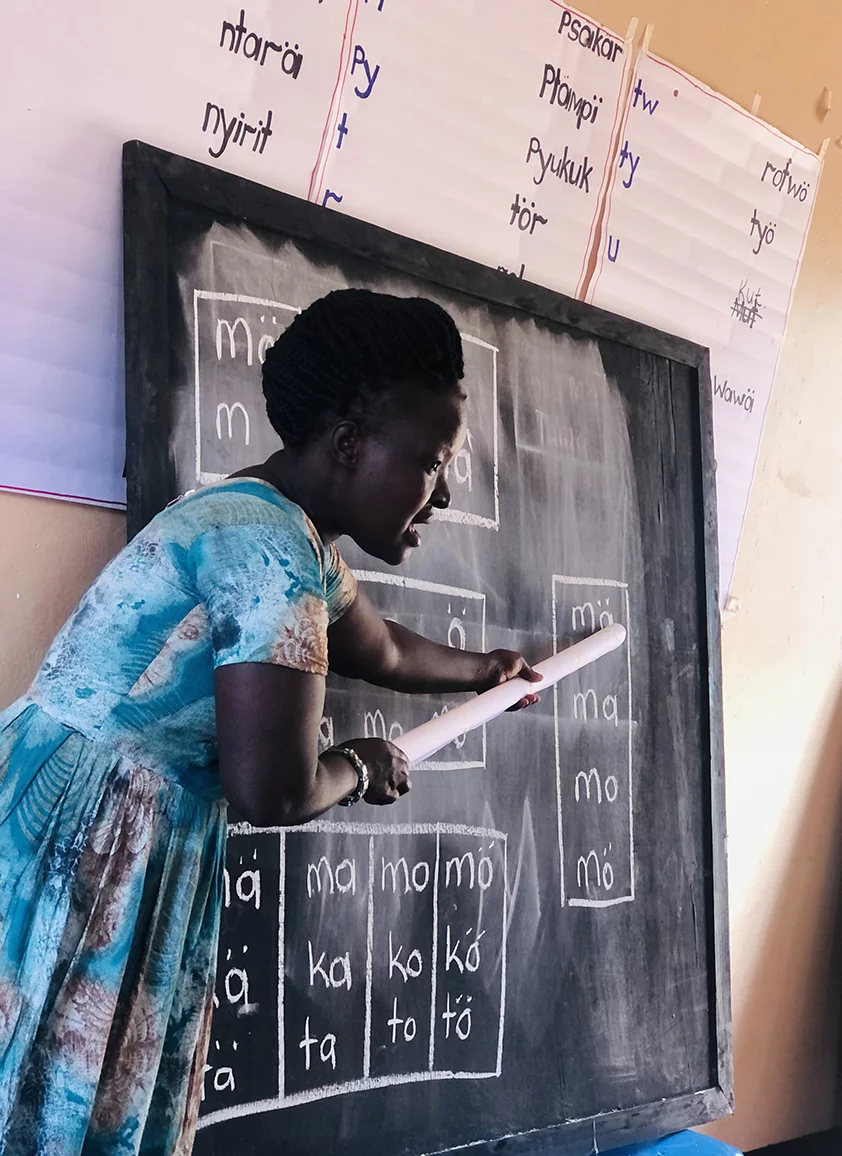

Kipkemboi goes into the classroom, settles down, and waits for the teacher to start. After roll call, the teacher begins the lesson. It’s something to do with learning to read, but Kipkemboi doesn’t really understand what’s going on. Neither do his friends.