Never stopped spreading

‘We found a niche with something that no-one was working on in Christian circles,’ Margaret explains. ‘And something we found that church leaders really appreciated.’ News about the impact of the course began to spread through word of mouth. And then more widely when it was first published as a book titled Healing the Wounds of Trauma: How the Church Can Help in 2004. ‘It never stopped spreading, with people frequently writing to us and asking how they could use it,’ Harriet remembers. ‘Within 10 years it was in over 100 languages and it had reached every continent.’ It continues to grow and spread – and different versions of the course for children, oral communicators, teens and for radio broadcasting have been developed.

Through the lens of the Bible

‘When we’ve talked with people we find there are many organisations, like the UN and other aid agencies, that come in and do a form of trauma healing,’ Cami notes. ‘But during our workshops people say “those courses never helped us like this.”’ Cami believes ‘that the number one reason for this is that the course is Bible based.’ She explains further that, ‘when mental health is taught through the lens of the Bible, with biblical support for the power of listening, biblical support for the power of writing laments, biblical support for the way we process grief, biblical support for bringing your pain to the cross – when you bring the Bible into it, it brings a supernatural power that people feel.’

Harriet also believes that it is this ‘fusion of the Bible with good mental health principles’ that makes the course so effective. ‘We have research by secular mental health scholars,’ Harriet explains. ‘Documenting that if you do trauma healing interventions without addressing the spiritual, it is not as effective.’

Of course, good mental health and the Bible are not separate things. As Margaret observes, ‘good mental health is in the Bible.’

Why, God?

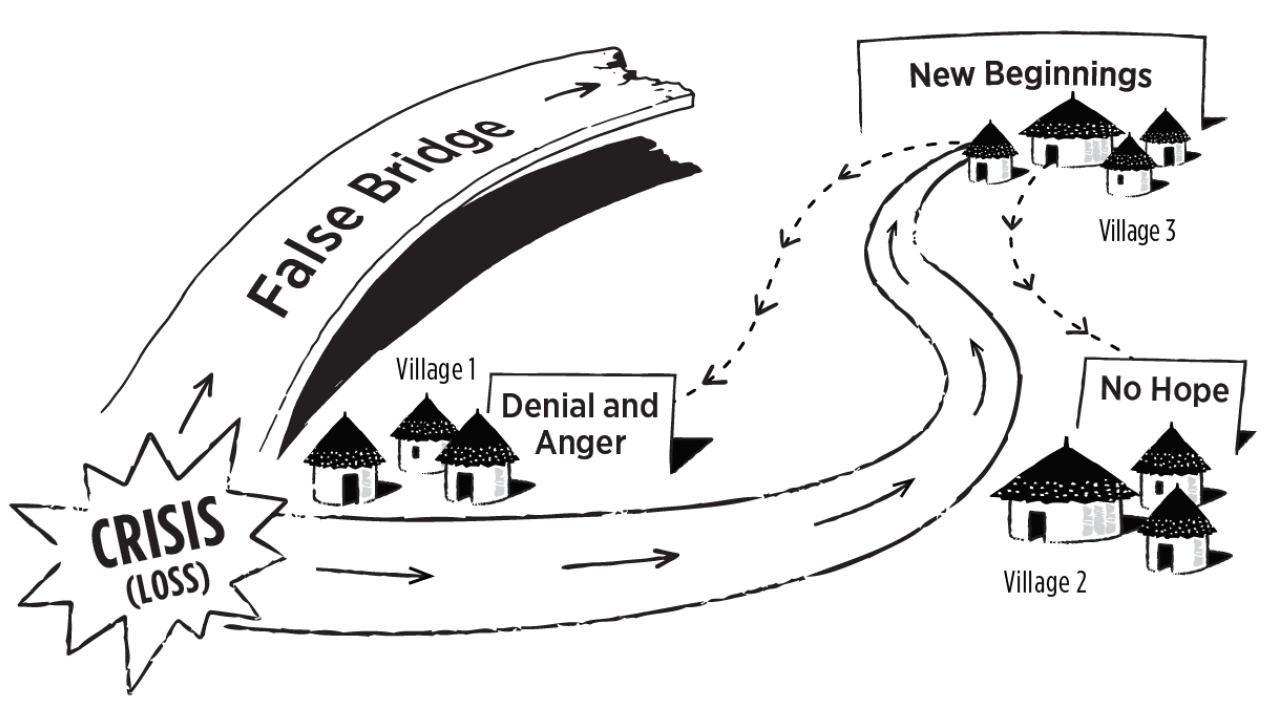

So how does the trauma healing course guide people on a healing journey through the teaching of the Bible?

‘It starts,’ Harriet explains, ‘with the pain, with asking “Why, God?”’

There are 16 lessons in the course. Five are considered ‘core’ lessons that are covered in every trauma healing course. The others can be used according to the circumstances of the people on the course.

The first core lesson asks: ‘If God loves us then why do we suffer?’ This lesson provides a vital foundation for the course. Cami explains, ‘if you do not deal with the theology of suffering first, then none of the rest of it makes any sense.’ This lesson invites participants to look at what the Bible teaches about the difficult question of suffering. And it leads participants to understand how, even in the middle of immense pain, God is close.