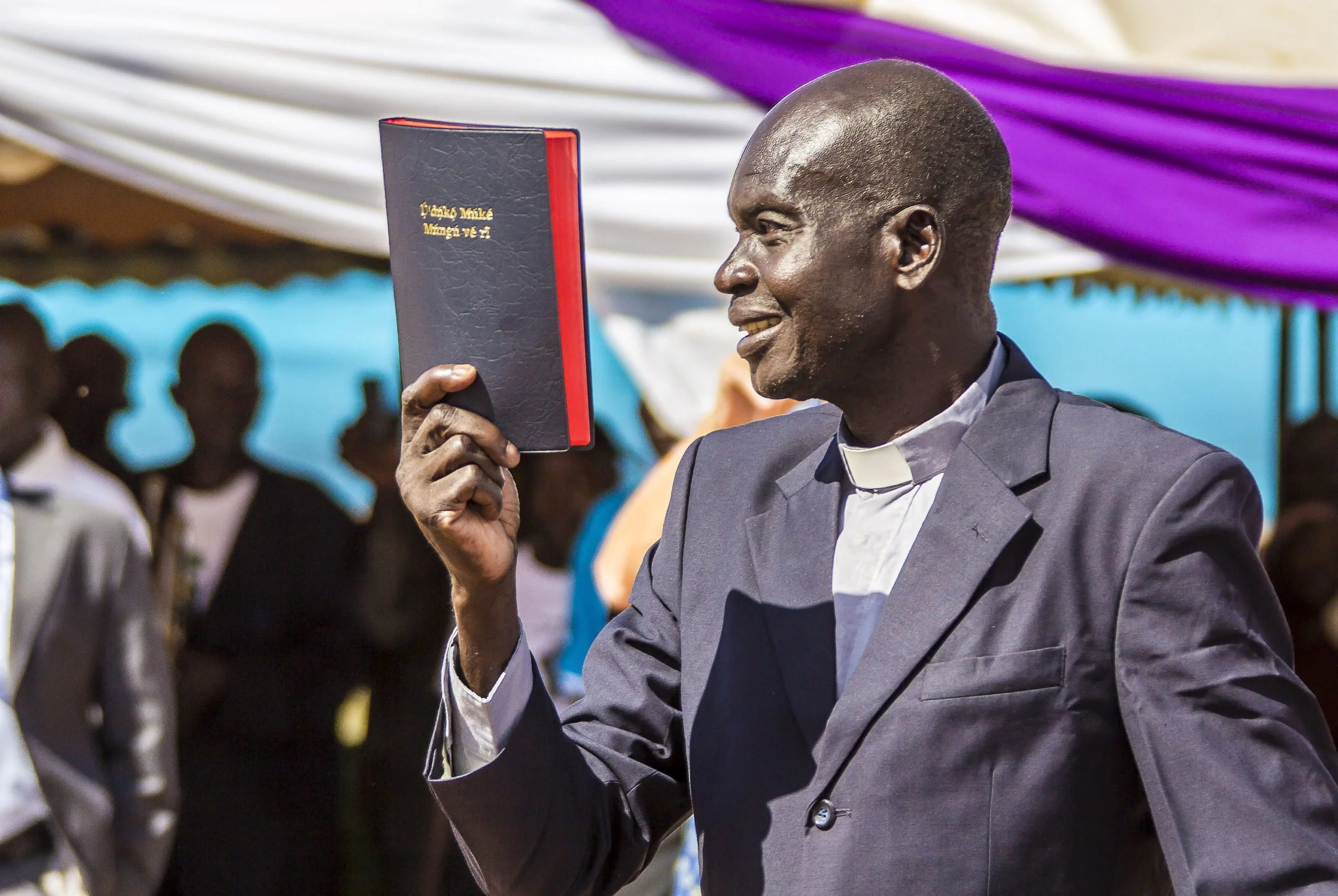

In August 2018 the Keliko people of South Sudan celebrated the launch of their New Testament in exile in northern Uganda.

Many are now living there in refugee settlements. It is the 1000th New Testament translation that SIL, Wycliffe’s primary partner, has been involved in. Behind the celebrations is a remarkable story of faith and persistence through the traumas of migration and war to bring God’s message of hope to the Keliko people.

In the early 1980s Rev David Gale found himself weeping at a conference near Juba, in what is now South Sudan. Pastors from many people groups attended the conference. And each pastor was asked to read a passage from the Bible in their language. Rev David came from the Keliko people. The Keliko were first evangelised in the early 1900s but their only access to God’s word came through Bangala or Bari, the neighbouring trade languages. So, when Rev David was asked to read the Bible in his language he couldn’t. Not one word of Scripture had been translated into Keliko.

Overcome with sadness

Rev David was so overcome with sadness that his people didn’t have the word of God in their language that he broke down and wept.

But he turned his tears into prayers. He asked those at the conference to pray that his people would be able to translate the Bible into Keliko. He also opened his trade language Bible and found Matthew 7:7 – ‘Ask and it will be given to you, seek and you will find, knock and the door will be opened to you.’

And asking, seeking, knocking is exactly what Rev David did when he returned home. He went around and gathered a group of Keliko people together to help him write the Keliko language, as there was no standard way of writing Keliko at the time, and to begin translating the Bible. So the journey to the Keliko translation began. But no one knew the difficulties that lay ahead for the Keliko people.