The Yewase* people of Burkina Faso discover the God who makes himself knowable

‘Now, how are we going to translate the name of God?’ asked Pastor Seko*.

‘Now, how are we going to translate the name of God?’ asked Pastor Seko*.

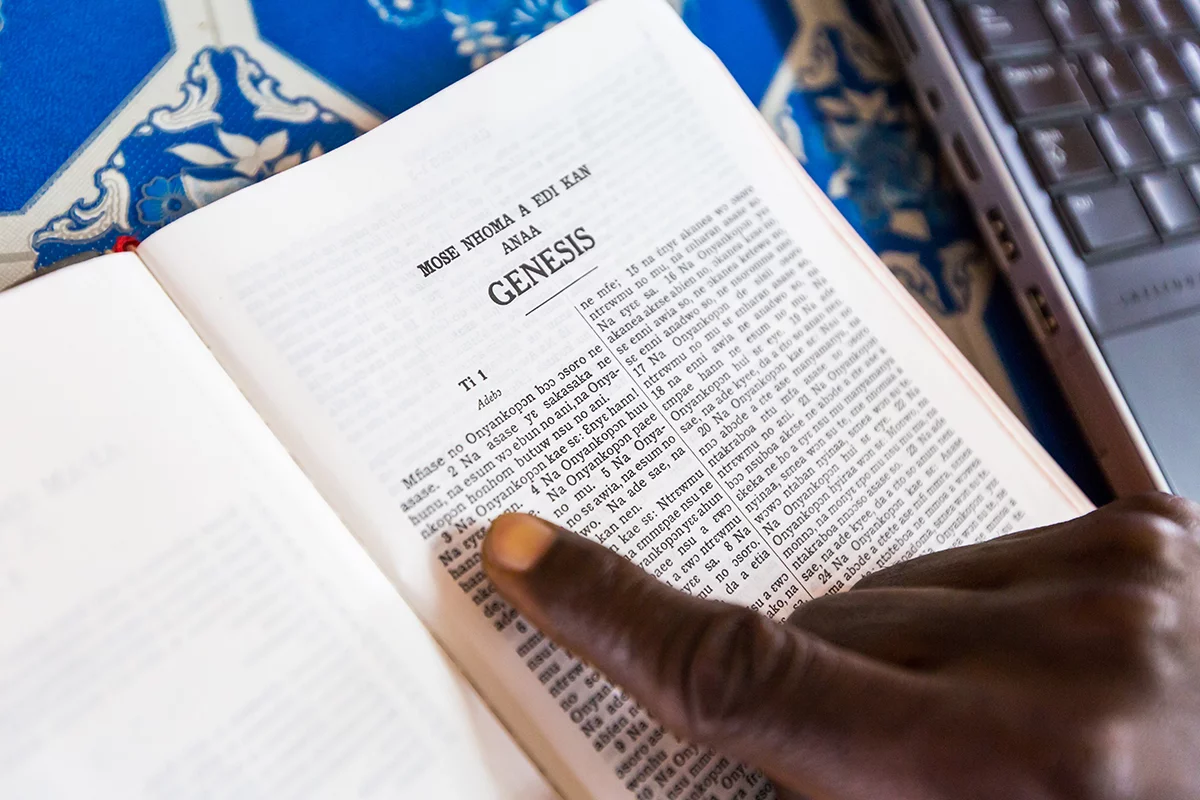

Having launched the Yewase New Testament in 2016, there was no question about which word the team would use for God: the word was Yékírí, which referred to God as the author of everything that happens to us. But this was the first day of work on the Old Testament. Now they needed to decide how to translate the Hebrew name of God: Yahweh.

When each team member was settled around the big desk, laptops ready, Pastor Seko began with this weighty question.

Most Yewase people followed an African traditional religion. They believed in one God, but that he was far away, unreachable, with layers of spiritual and human hierarchy between him and them. Each person’s responsibility was to do what the religious representatives required: make the sacrifices; pray to their ancestors; perform the correct burial rites. How could they even dream of knowing the true God for themselves?

Pastor Seko knew that the word they chose to translate the Hebrew name of God, Yahweh, would be important. It could influence whether his people saw God as distant or close; knowable or unreachable; for them or only for other people groups.

Rosemary Pritchard, from the UK, was the newest member of the team. In fact, this was her first day. Her story began in the ’70s, when she sensed God calling her to Bible translation. ‘It felt like a Rosemary-shaped thing,’ she says. ‘But back then there was a very firm “no” which came out of my circumstances.’

The Yewase celebrate the launch of their New Testament

The Yewase celebrate the launch of their New Testament Eventually Rosemary became a Methodist minister, and used her love of languages to study Greek and Hebrew. She even had the chance to spend a year researching West African translations of the name of God.

But it wasn’t until 2014, 38 years later, that God opened the way for her to serve him in Bible translation – and then to join the Yewase team in Burkina Faso.

Pastor Seko’s first question to Rosemary, on her very first day working with the team, was about the very subject on which she had written her dissertation – an incredible confirmation that she was where God wanted her. But this was only a first glimpse of his goodness at work.

So how would they translate the Hebrew name of God, Yahweh? The answer actually came quite quickly. Rosemary is still amazed when she remembers: ‘Do you know what? They had a name. They had an obscure name for God in their language: Yáawérí.’

This name was strikingly similar to the original Hebrew – but did it have the right meaning? It wasn’t used very much in everyday conversation. Would Yewase speakers who followed the traditional religion understand it? Early on, the team translated the story of Joseph. When they had finished, it was time to find out by testing it with members of their community.

Since the villagers were only free after they had finished their work in the fields, everyone gathered at night. There was a sense of great attention in the darkness as the chapters of Genesis were read. The younger community members were fascinated – but deferred to their elders as one of the team started asking questions.

Finally, he turned to one of the men and asked, ‘Who is Yáawérí?’

The man hesitated, thinking back to when he had heard the name before. ‘Now… that’s the name of the true God… isn’t it?’

Pastor Seko, never a demonstrative man, was quietly satisfied. This was exactly what they had hoped for. What might these stories from the Old Testament mean to this man, and to all of the Yewase people, now? How would it transform their understanding of the Christian story – the story not of a God who is far away, but of the true God with us?

The Yewase word had been there all along, but it took this team of translators to release its potential – to show that we can know God by name, and have a relationship with him.

*names changed for security reasons